During the latter part of the nineteenth century, London streets were home to a variety of small residential institutions: hospitals, schools and orphanages. Some grew and prospered such as Hampstead General Hospital, which began in a single house, later moving to a large site off Haverstock Hill and was absorbed into the Royal Free after WW2. Others were short lived, lasting as long as there were funds or interest in the project. This is the story of one charitable home for children in Kilburn.

143 Carlton Road

143 Carlton Road

(later renamed Carlton Vale) was a Victorian villa, built in the late

1850s/early 1860s. It stood close to the junction with Peel

Road. This area has been comprehensively

redeveloped and most of the old houses, including number 143, have been

demolished.

|

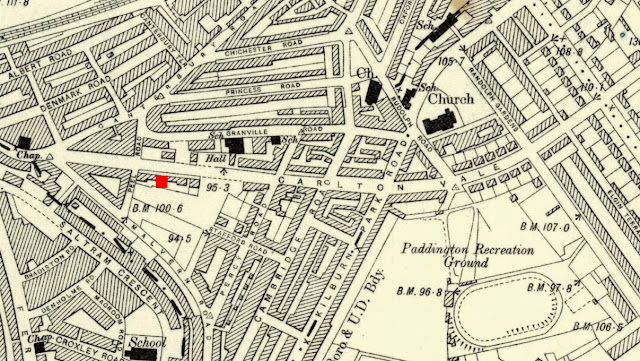

| 1890s map showing the position of 143 Carlton Road in red |

In 1869, a young Hubert von Herkomer who was to become Sir

Hubert, a noted painter, engraver and etcher, was lodging with the family of a

fellow student at 143 Carlton Road.

He exhibited his first picture at the Royal

Academy, ‘Leisure Hours,’ from this

address. It was a portrait of his friend’s sister, in an old fashioned silk

dress, looking at a sketch held at arm’s length. Herkomer attended the Royal Academy

soiree in a dress suit rented for the evening from a pawnbroker for ten

shillings and sixpence. The lodgings didn’t work out and he soon left Carlton

Road for new digs in Chelsea.

|

| Herbert Heckomer, self portrait c1880 |

The 1871 census has a bus driver and his extended family

living at number 143. Properties in the south Kilburn area often experienced a

regular turnover of tenants, many of whom are untraceable as they don’t appear

in either the Rates or the Census.

In 1881, the house stood empty but soon after, it became a ‘House

for Homeless Infants’. There’s little surviving information about this

establishment; for example, the entry criteria: was

the baby abandoned or orphaned? An 1887 report said, ‘babies who have fallen on evil times are received and nursed back into

health and strength’, which could reflect either of these possibilities. It

continued: ‘This little home is the

special care of Lady Stanley and has for six years past been principally dependant upon her for the funds necessary

to carry on this good but unpretending work.’

Lady Stanley

It seems likely that Lady Stanley set up the Home. Her level

of support strongly indicates this was the case: ‘Lady Stanley is at the Home, eleven to one, every Wednesday morning,

and is especially pleased to show the Home and its little inmates to all who

care to call between these hours.’

Lady Stanley was born Lady

Constance Villiers. She married Frederick Arthur Stanley in 1864. He was known

as Frederick Stanley until 1886 and as Lord Stanley of Preston

between 1886 and 1893, when he succeeded his brother as the 16th

Earl of Derby. Constance, described as an ‘able

and witty woman,’ was on the first Grand Council of the Ladies Branch of

the Primrose League, an organization dedicated to upholding the Conservative cause

and spreading its principles. She supported her husband in his political

career, in particular as Governor General in Canada. In this age before women’s suffrage, Constance

needed her husband’s permission to involve herself in the Home. She was in a

strong position to forward its aims: in 1886 the funds received a welcome boost

from the proceeds of an evening’s theatrical performance. The following year a

fund raising concert was held at the Stanley’s

home, 5 Portland Place, a

large, double fronted property close to Langham Place.

The 1887 Fundraiser

Several of those on Lady Constance’s concert list also

performed and if they didn’t directly support Lady Stanley in her patronage of

the Kilburn Home, part of their work involved children. Alfred Scott-Gatty was

a composer with a special interest in promoting

music for children.

Mrs Henrietta Stannard not only recited, she also sold

tickets for the event. Henrietta wrote stories, mainly centred on army life,

under the pseudonym of ‘John Strange Winter’. Her reputation was established by

‘Bootle’s Baby’ and ‘Houp-La,’ both of which appeared in

The Graphic in 1885. For the Kilburn fund raiser Henrietta read ‘The

death of Houp-La’. The setting was the Egyptian campaign of 1882.

Houp-la is a poor uneducated boy devoted to his master, who has the difficult

task of delivering some important dispatches. Houp-la takes the dispatches and

after overcoming many dangers, he delivers them safely and is much praised for

his bravery. But on returning to camp, Houp-la is ambushed by the enemy; ‘a search party organised for his relief, find

him, but too late. Houp-la returns to die in the arms of his master.’

Such sentimental tales were very popular at the time. In ‘Bootle’s

Baby,’ an abandoned baby is eventually reunited with its mother who marries Captain

Algernon Ferrars, otherwise the ‘Bootle’ of the title. Two

million copies were sold during the ten years following its first publication.

What happened to the

Home and Lady Stanley?

The Home had closed by 1891, when number 143

Carlton Road is shown in the census as subdivided

and occupied by four families. Its closure is likely to have coincided with Constance’s

departure from England

in 1888, when her husband took up his post as Governor General of Canada.

She continued her charitable work there, founding the Lady Stanley Institute or Trained Nurses, the first nursing school in Ottawa. The couple

returned to the England

in 1893 where Constance died in 1922. Her obituary in

the Times made no mention of her philanthropic works.

|

| Lord Stanley |

What happened to the infant inmates after the Home closed is

not known.