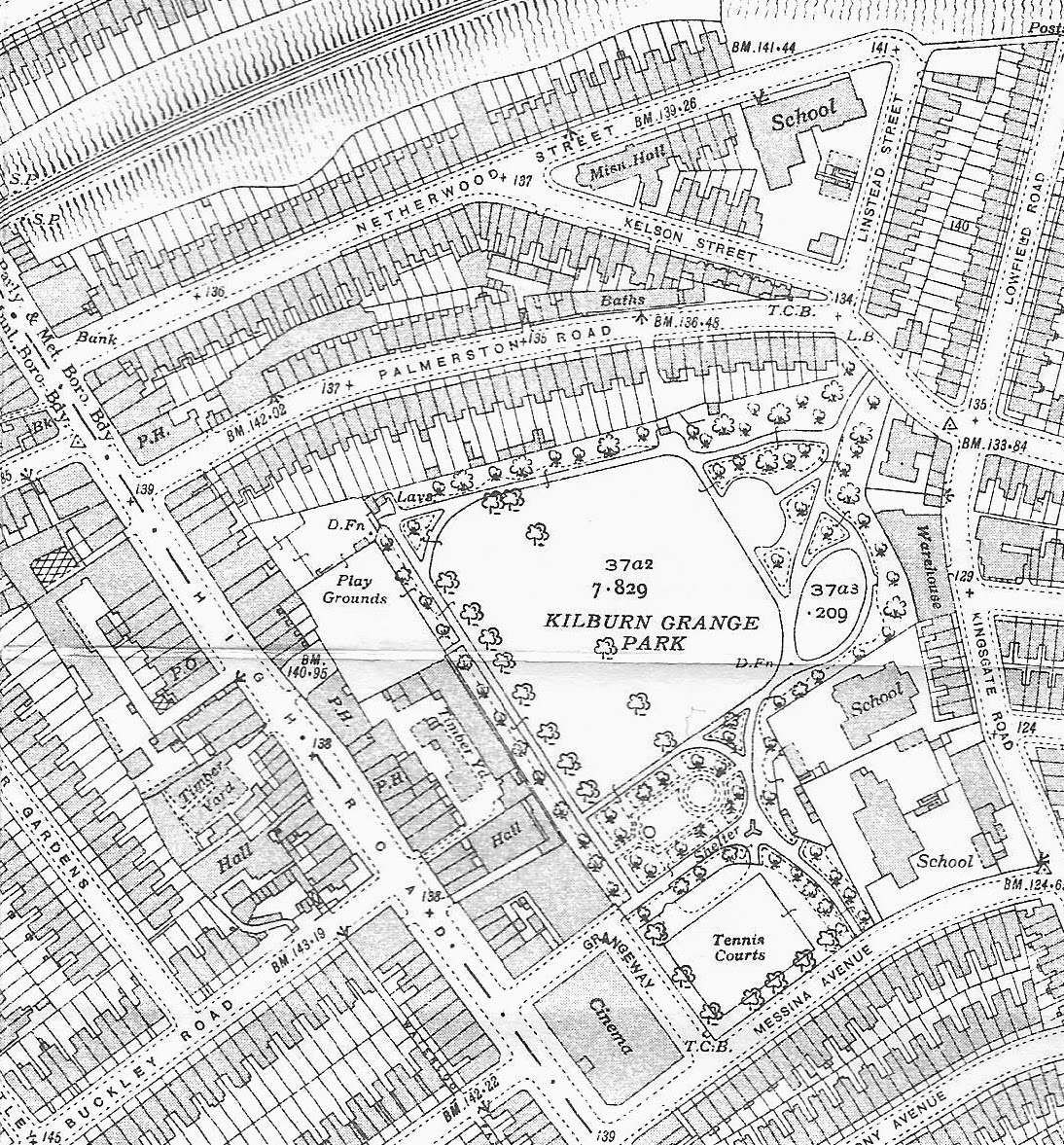

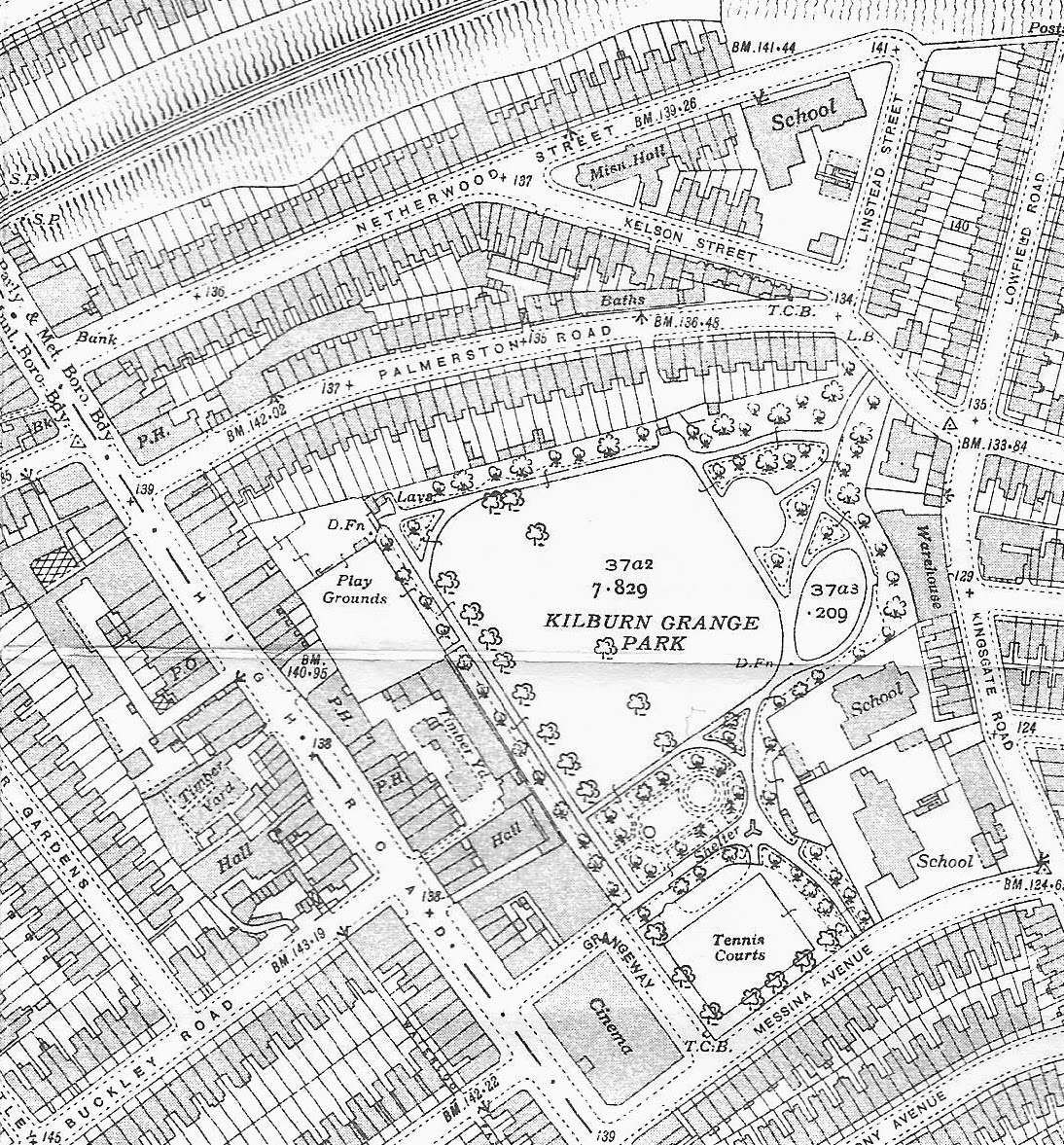

Netherwood

Street was a poor

street running off Kilburn

High Road, as

shown at the top of this 1935 Map. The Mission Hall and the Board School can be clearly seen on the right hand side. Today, most of

it has disappeared and is covered by Webheath, a large block of council flats.

|

| 1935 Map of Kilburn |

The United Land Company auctioned off

plots of land to various small builders and Netherwood Street was constructed between 1871 and 1880. There were at least thirteen different

builders at work in the street. Some were based in Kilburn, but addresses of

others range from Holloway and Notting Hill to Berkeley Square.

The properties in Netherwood Street were for the most part three-storey terraced houses, some with

a basement. A few had shops at street level. They were generally owned and

rented out by absentee landlords, who regarded the properties as an investment

but often lacked the funds to manage them properly. As soon as they were built,

the houses were multi-occupied by poor families and disease and deaths were

common in the area. Frequently four families shared a house so there were 20-30

people in each. As was the case elsewhere in Hampstead, until enough houses

were built, the roadway remained a dirt track, which caused more problems for

the residents and owners.

The Vestry Minutes of Hampstead (the precursor of the

Council), show examples of disease and poor housing in Netherwood

Street

1874 November

The ‘new buildings’ in Netherwood Street are in bad sanitary condition. There are many complaints

to the Medical Officer of Health about illness in the street.

1877 October

There are three deaths from

scarlet fever in one house.

1879 May

Owners and occupiers press the

Vestry to pave the road, ‘also stating it

would be a great improvement if the name were altered to ‘Netherwood Grove’,

trees having been planted on both sides.’ (The use of such descriptions as

‘Grove’ or ‘Avenue’ put people in mind of more rural and upmarket properties).

1881 August

The house owners had to pay the

cost of paving and kerbing the road in front of their properties. Francis

Holmes was a newsagent with premises in Chapel Street near Cavendish Square. He owned several properties in Netherwood Street and was being taken to court for failing to pay his share

of the paving and kerbing costs.

1882 August

Two deaths from measles.

1884 June

The London smallpox epidemic. There are seven cases at 29 Netherwood Street, one adult and six children. The 1881 census shows 25

people living in this house.

1884 October

Rent collector G. H. Cooper was

summonsed for failing to carry out repairs on four tenement houses in Netherwood Street, owned by a Mr Holmes who did not appear in court. But no

further action was taken, as work was being carried out. Cooper went on to

describe the ‘serious state of things’ in the road, notably the main sewer,

which was the responsibility of the Parish. He said that one of Mr Holmes’s

tenants had complained several times of a flow of sewage into his basement, and

this had also happened in other houses.

1885 March

The rent collector again appeared

in court on behalf of his employer. The sanitary inspector had investigated Cooper’s

allegations. Unfortunately for Mr Holmes, the main sewer was fine. The overflow

was down to a defective drain at Number 31, one of the houses he owned in the

street, and the landlord’s responsibility to repair.

The sanitary inspector described

visiting Number 31, home to four families, on 5 February. He found ‘the drain

stopped up and sewage floating about in the front area’ and despite issuing an immediate

order for repairs, the drain remained partly blocked. The road and pavement had

to be dug up at the cost of the landlord, which probably explains why the work hadn’t

been done.

1886 January

Two measles and one scarlet fever

death.

1886 March

A measles death.

1886 July

Infant deaths from diarrhoea.

In 1896 the Hampstead Medical

Officer of Health reported that an epidemic of measles had attacked the streets

in the vicinity of the new Netherwood

Board School. Eleven fatal cases occurred between 25 December 1895 and 8 January 1896.

Most of the children were under two years of age, the eldest was five. The

deaths were caused by secondary infections of bronchitis and pneumonia. ‘The disease was only fatal to the children

of labouring classes, a fact which points to a want of either care or of means

in its treatment.’ At the time there was very little free medical care.

1898 June

The late Victorian standards of

what constituted adequate housing were far less exacting than today’s. This is

shown in a report by Hampstead’s Medical Officer of Health on conditions in Netherwood Street and neighbouring Kelson Street and Palmerston Road. He concluded most were in ‘fair sanitary condition and not overcrowded.’ The houses were

almost all in multiple occupation with sanitation largely dating from the day

they were built. The water supply was now judged ample as was the number of

toilets, (no figures per house were given). ‘The best kept houses were those which had a responsible landlord, that

is one who rents the house and carefully sub-let it. The worst kept were those

where the owner did not reside on the premises, but called to collect the rents

weekly by self or agent.’

A total of 160 houses were

examined, home to 2,264 people of whom 668 were children under 10 years of age.

In May 1910, during a campaign to

purchase the grounds of ‘The Grange’ as a much needed open space for Kilburn,

the following appeared in the Times.

The death rate in Hampstead generally is the

lowest of any borough in London, 9.5 (per 1,000)

but the death-rate in the Netherwood Street area just

adjoining The Grange, with a population of 3,049, is 16.8. The phthisis (TB)

death rate in Hampstead generally is

0.74, while in the Netherwood-street area it is 2.09.

The 1881 census

Most people in Netherwood Street were working class. In the 1881 census the men worked as;

tailors, cab and omnibus drivers, gas fitters, or in the building trade as

plumbers, bricklayers and carpenters; others worked for the railway as porters,

signalmen, or platelayers. The women had jobs such as; laundress, barmaid,

domestic servants, charwomen, and dressmaker. Many families rented space to lodgers

or boarders.

But there were a few people with more

unusual occupations such as the following:

The Honourable Francis Henry

Needham was sharing Number 2 Netherwood Street. He was the son of 2nd

Earl of Kilmorey. The Earl went by the nick-name of ‘Black Jack’ and

sensationally ran off with his ward and had a child by her. Francis married

Fanny Amelia Hubbard in 1840 and

they had six children. She died in 1884. It is not clear why Francis Needham

was living in Kilburn in 1881 and 1891. By the 1901 census he had moved to

Paddington, now aged 82 and shown as ‘feeble minded’. He died the following

year.

At Number 10 was Kate Middleton,

an actress listed as ‘retired tragedian’.

Henri d’Archimbaud, a Professor of

French Literature, was sharing Number 49.

William Wallace Leitch,

watercolour artist, was at Number 67. He was the son of a famous Royal Academy artist, William Leighton Leitch, who lived at 124 Alexandra Road.

Two Nottinghamshire born men, Charles

Boot and Tom Gregory, were lodging at Number 81. Both gave their occupations as

bootmakers – which was their original trade - but they were also talented

cricketers, employed as groundsmen at Hampstead Cricket Club.

Child Neglect

We found two sad newspaper reports

of child neglect due to poverty, and one case which legally involved neglect but

had a positive outcome.

In 1880 Thomas Gregory, a

commission agent, was accused of deserting his three children and jailed. They’d

been pupils at what was described as a ‘boarding school’ run by Emily Mayes at 49 Netherwood Street, (where Henri d’Archimbaud above, also lived). The fees were

a guinea a week and Thomas failed to pay. He didn’t answer any of Emily’s

letters so when he was ten weeks in arrears, she asked the parish authorities

to have the children taken to the Workhouse. A warrant was issued for Thomas’

arrest. He told the magistrate it was all a mistake, he’d been travelling and

not received any letters. ‘Upon the

children being brought into court there was an affectionate greeting.’ They

left the court together, after Gregory’s debts were settled – by his friends.

In May 1884 a tragic case was

reported, when nine month old Jane Shepherd, who lived with her family at 16 Netherwood Street, died. She was a twin, one of five children. Her father

was in regular employment as a bricklayer and did all he could to feed them but

her mother ‘was in the habit of giving

way to drinking bouts lasting four or five days at a time, and during those

periods the children were very much neglected’. As a result Shepherd kept

his eldest child (a boy aged only 8 years), at home to look after the others.

When baby Jane developed

bronchitis, her mother applied a poultice and got some medicine from a doctor.

But then she disappeared for three days on another drinking binge. Even though

her father continued giving her medicine, Jane died. She only weighed 7lbs 6oz,

roughly the weight of a new born infant. At the inquest the mother said she

hadn’t gone home because she’d lost her purse and was afraid of her husband.

The jury decided the baby had died of exhaustion and wasting following

congestion of the lungs, and that Jane’s death was accelerated by the neglect

of her mother, for which she was answerable. The coroner told her she’d had a

narrow escape from being committed for trial. The father put all the other

children into the workhouse.

In October 1887 James Crawley, 35,

a coal porter living in Cambridge Mews was charged with deserting his four

children aged 2-15. They were found ‘in a very neglected and dirty condition’ in

a house in Netherwood

Street, where

they had been living on their own for 10 days. Neighbours had been feeding them

and told the magistrate the mother had run off with a man, no one knew his name.

The children had been removed to the Workhouse, where now only one remained.

The oldest girl Catherine, said to be ‘rather simple’ had been found a job and

two of her siblings had been sent away to school. So far the children had cost

the parish £5 15s 3d. Sergeant Forde 43S, said he apprehended the prisoner,

James Crawley, on Rosslyn Hill.

Crawley said he hadn’t deserted the children, but left them in Catherine’s

care with a 1s or 1s 6d a day to pay for their food. He promised to pay back

all the money owed to the parish, if the magistrate allowed him time to do so, and

his parents were willing to look after the children. Crawley was

sentenced to one month’s imprisonment with hard labour. No record of what

happened to the children survives, but the 1891 census has a Catherine Crawley

of the right age, working as a laundress in St Michael’s Convent near Southampton.

This could well be James’ daughter.

Netherwood Street Board School

This opened in November 1881 and was

built by the London School Board, a body established to make certain even the

poorest children got an education. There were 18 classrooms, for about 1,000

girls, boys and infants. The first headmistress was Mrs Adams, whose husband

was the headmaster of Fleet Road School, Hampstead’s first Board School. Netherwood was the second Board School to open. Inspector’s reports on Netherwood

School were good. In 1883 The London School Board Inspector said,

‘the school was in excellent order’,

having passed ‘a very creditable

examination’. After two years Mrs Adams left to become headmistress of the

newly formed Junior Mixed Department at Fleet Road School, where her husband became head of the senior school.

In 1891, Emma Brennan was in

court, accused of assaulting the headmistress, Harriet McGregor. Emma lived

nearby at 1a Hemstal

Road, (where the six

members of the Brennan family occupied just two rooms). The headmistress said Emma

had come to the school and abused her daughter’s teacher, Mrs Rowland. When asked

to leave, Emma had twisted Mrs McGregor’s arm so badly she had to wear a sling

for several days. She left but returned later in the day, saying this time, ‘20 gentlemen would not put her out’. Why

was Emma so angry? She told the court her daughter had gone to school as usual

but been sent back to collect her school fees. Emma decided to keep the child

at home until it was time for afternoon classes. Meantime another pupil from

the school arrived at the Hemstal Road house, with a message demanding Emma’s

daughter return immediately, bringing the fees she owed, otherwise Mrs Rowland would,

‘cane her until she could not see.’ Emma,

indignant at receiving this message, said she went to Netherwood Street to confront Mrs Rowland, but she denied the assault. The court

was told the message was incorrect and the magistrate ordered Emma to find a

surety of £5 to keep the peace for three months, with 21 shillings costs. He

further remarked ‘that teachers required

protection against some mothers, but (he recognised the irritating nature of

the message Emma had received.’

Warwick Edwards attended the

school in the years before WWI. He wrote:

We were a very mixed but pretty happy lot

there. The Headmaster Mr Lembleby, was short and stocky but of considerable

dignity. He was assisted by an able, hard-working staff. I had the good fortune

to be for several years in Alfred Oakley’s class. He was one of the most

outstanding men I have ever known. In addition to the basic three ‘R’s he told

us much about English history, Bible history and even Church history, He also

taught us geography, singing and a smattering of science. He was in his forties,

well-built and was a good swimmer, a good footballer and a wonderful bat. The

schoolmaster was there to do a job – to teach us the elements of knowledge, and

by heaven, he did it well. Wrongdoers were dealt with in a firm manner, of

course, but there was much less recourse to the rod than some people believe. I

had the cane on two occasions only; first, when with perspiring hand and a

rubber that went berserk, I made a ghastly mess and rubbed a hole in my drawing

book; and second, when I persisted in talking to the boy sitting next to me, I

do not disagree with the judgment of the court in either case.

The school was reorganised and

renamed ‘Harben Secondary School’ in 1931. In 1961 it became the lower

school of St George’s Roman Catholic Comprehensive, Lanark Road, Paddington. After St George’s left, the building was damaged by an arson attack and in

1996 was sold to developers by Westminster Council. It is now ‘Oppidan

Apartments’, but plaques on the exterior remain, reading ‘School Board for London’ and ‘Netherwood

Street School’.

The St James Mission Hall

As early as 1869 the London City

Mission had appointed a man to work in the poor Kilburn streets of St Mary’s

parish which later formed part of St James’s parish. In 1875 St Mary’s opened a

mission room in a house at 7 Palmerston Road. The 1881 census shows Annie Elizabeth Beattie, a 55 year

old ‘mission woman,’ was living there. That year St Mary’s commissioned a

mission hall, designed by Arthur Blomfield, which was built at the corner of Netherwood Street and Kelson Street by the firm of Samuel Parmenter of Braintree, Essex. The cost was £4,531, which is equivalent to about

£360,000 today.

The mission hall was taken over by

St James Church in 1888 when the new parish in the rapidly growing area was

created from St Mary’s. It was called ‘The Mission Rooms and Institute’ and the

manager was Rev. James William Hoste, a curate from St James.

In 1890 at a meeting in the

Mission Rooms, local MP Bodie Hoare said the object of the Institute was to,

‘get

hold of the strength and vigour of the youths, and to train them into leading

wholesome, proper and useful lives.’

The Hon Alfred Lyttleton who was

the President of the Federation of Working Boy’s Clubs, said that boys,

‘were not to be discouraged if in connection

with other clubs they were beaten, but to win victories without swagger, and to

take their ‘lickings’ with generosity.’

The 1891 census shows husband and

wife Clifford and Isabella Nairn, as the caretakers of both the Netherwood

Board School and the Mission Rooms.

The Mission was also active in the Temperance Movement, as the

following article from the Middlesex Courier of 27 January 1893 shows. At the time, the ‘demon drink’ was a major problem

among the poor and working classes, and the Church encouraged ‘temperance’ or

abstention from all alcohol.

Perhaps one of the most, if not the most

successful branch of the Church of

England Temperance Society (CETS)

is that held in St. James’ Mission Hall, Netherwood Street, Kilburn. In this

large hall entertainments for members and their friends are held every Monday

evening and are well patronised and thoroughly appreciated by the neighbouring

residents. Situated as this hall is, in the very midst of a densely populated

portion of Kilburn, that includes many of the very poor, it is no wonder that

these entertainments are so thoroughly appreciated by every one. Concerts,

lectures and dioramic views are all given and all form a source of great

pleasure to many. It was our privilege last Monday to be present at one of

these entertainments. We found the large hall crowded to its utmost, many

having to stand, but all seemed to be thoroughly enjoying themselves. The

audience was composed almost entirely of the poorer working men and their

families. The entertainment on this occasion was a series of dioramic views,

illustrating life in East and Central Africa. The views were

explained very graphically by the Rev. J. Hayes who succeeded in combining

instruction with amusement. Illustrated by another series of views, an

admirable object lesson on the value of Temperance was read by Mr Carrodus.

Warwick Edwards remembered the

neighbourhood in the years leading up to WWI.

Netherwood Street and Palmerston Road were

distinctly plebeian, even tough, in the 1900s. One could not help feeling that

those who had built the Mission Hall did so in the spirit of those earnest

Victorians who sought to bring enlightenment to darkest Africa. If so, their

success was limited. Beer was cheap and the shortest if only temporary escape

from a drab existence was, for many, through the door of the public bar. Street

brawls, particularly on a Saturday night, were a regular feature. Domestic

squabbles were not always carried out in the seclusion of the home but

sometimes in the street, to the amusement (or embarrassment) of passers-by. The

police did not intervene unless grievous bodily harm seemed imminent. A sad

feature of the time was the occasional unceremonious dumping, by the broker’s

men, regardless of season or weather, of the pitifully scanty household effects

of the feckless or unfortunate families that would not or could not pay their

rent.

During the 1950s, the Mission Hall

housed a popular youth club and local resident Dan Shackell said he played

table tennis there with the ‘Tennyson Club’. In February 1958 he vividly

remembers hearing over the Tannoy about the Manchester United disaster at Munich airport.

Other youth organisations also

hired space. There wasn’t much for young people to do locally that didn’t cost

money, and there were few outlets for their energy. Sometimes there were problems. On

22

October 1958 the vicar of St James

reported that he was appalled by the damage (unspecified) caused by members of

the ‘Achilles Club’. The parish church committee agreed the Club had to leave.

The ILEA Phoenix Youth Club took

over the St James Mission Hall with a full-time leader on weekdays. On 27 June 1960 the police were called when members of the ‘Phoenix Club’

were fighting and using bad language. Miss Shepard, the club manager, said the

incident happened when a group of youths from outside the district were refused

Club membership, but turned up at the Hall and weren’t allowed in. She denied

that fighting took place. In June there were reports from neighbours about

noise from the Club’s record player on summer evenings because the windows were

open. On 7 September 1960, when

members caused more damage, the Club was asked to pay for the repairs, (no

figures are given).

In July 1966 the vicar reported

the sad loss to the Mission Hall caused by the death of the caretaker, Kathleen

Mann. It was also reported that the Council were negotiating to buy the site.

Mrs McKenzie, who ran a nursery there, said she would leave at the end of July.

The Church gave up the Hall on 15 May 1967

and it was demolished, its site absorbed into Camden’s redevelopment of Netherwood Street and the surrounding neighbourhood.

Murder or Manslaughter?

In 1961 Arthur Lewis Vincent

Wells, aged 18 was charged with murdering his girlfriend, Josephine Holditch,

also aged 18, a typist living locally with her family in Kelson Street. Vinnie Wells had grown up at Number 61 Netherwood Street

and had become a merchant seaman. At the time he was sharing a flat with his

friend Terry Phillips in Gascony Avenue.

Detective Chief Inspector McArthur told the magistrate’s court

that on Thursday night 26 January, Josie had come to

the flat and Vinnie had pointed a gun at her head. Josie had told him to put it

down, but he pulled the trigger twice and she died from a bullet wound in the

head. Vinnie, horrified at what he had done, went to the police station and

gave himself up. As CI McArthur was giving evidence, Vinnie seated in

the dock cried out, ‘Oh my Josie, my

Josie’. He was sent to Brixton prison on remand. But that night Vinnie was

found unconscious in a room in the prison hospital after trying to hang

himself. He died three days later.

When his barrister, Edgar Duchin appeared at Marylebone

Court four days later, he said, ‘Wells had taken his life out of remorse

rather than fear. I was satisfied that, had he lived he would have had a full

answer to the charge of murder’. The magistrate agreed that the murder

charge be withdrawn.

Les Smith, who lived at Number 26 Netherwood Street, where his

parents ran a general shop, and who knew Vinnie well said:

The accepted story was

that Vinnie and Terry acquired the guns and ammo in order to rob a bank, Josie

was unhappy about the guns and visited Vinnie to break off their relationship,

quick to anger he shot her once in the head then gave himself up to the Police.

He hanged himself in his cell while on remand and died shortly after. Terry

went to gaol for possession of firearms and ammo.

Redevelopment

Today Netherwood Street is covered by Webheath, the large council estate, which

took many years to get approval. In August 1957 there was a heated debate

between Labour and Conservative members of Hampstead Council, over the ‘damp and decaying houses’ in Netherwood

Street, Kelson Street and Palmerston Road, home to more than 1,000 persons, 200

of them children under 5 years old. The properties were still in multiple, floor-by-floor

occupation and persistent flooding had resulted in some basements being bricked

up. ‘The slime used to get up to the

mantelpieces in some places’ said Alderman Florence Cayford, a long-time

campaigner for improving the living conditions of Kilburn residents. She asked the

meeting,

I don’t know how many members of the Council have visited

these houses. Can you imagine a tiny sink in the corner of the stairs that has

to be used by two or more families? It’s all the water they’ve got. You wonder

how these families can go out looking so neat and tidy and clean. There are

still homes with only one lavatory for all the families to use.

Redevelopment didn’t get underway

until May 1968, when Dame Florence (as she then was), watched the foundation

stone being laid. Two years later, she opened the first stage named in her

honour as the ‘Florence Cayford Estate’, later becoming ‘Webheath’.

Dave Unwin who worked as a Council

surveyor remembers working on the redevelopment.

Dave Unwin’s memories of Netherwood Street

By 1966 I had qualified and left

Brent to work for the London Borough of Camden as an Assistant Builder’s

Surveyor. Around 1972 we were undertaking a redevelopment in Netherwood Street. The site boundary was the front garden walls of the

houses on the north of Palmerston

Road and the

other side of the road was still occupied. The houses were three stories plus a

basement with a 'flying' staircase up to the front door. They were built in

what we called ‘cross wall construction’. The roof sloped from each of the side

cross walls forming a V valley across the house

At the time we had had a long hot

summer and one weekday in August around four o'clock

we heard a terrible rumble which we immediately realised was the collapse of a

building. We raced round to Palmerston Road to find that in the hot summer the cross walls had

expanded and pushed the front parapet walls down. As they fell they landed on

the front door staircase and took those out as well.

We called the Emergency Services

and barricaded off the street. God works in mysterious ways. Half an hour

earlier there had been 12 - 15 kids playing in the street, but luckily they had

all been called in for their tea, and the street was empty. When the Fire Brigade

arrived one appliance parked in front of the damaged houses. The Fire Chief was

on the opposite side of the road making notes. I noticed that where the parapet

walls had broken away the parapet was leaning, and suggested to the Chief that

he should move his appliance. He had just started writing in his book, 'At the suggestion of Mr Unwin, Surveyor for

Camden Council...' When I heard “Jesus

Christ” and the driver ran down the road and shifted the vehicle.

If such an occurrence happens in

most Boroughs it is the responsibility of the Council Building Surveyors to

decide what has to be done to a house to make it safe. But this is not the case

in the old London County Council area, where the District Surveyor (DS) is

responsible. We phoned him and when he arrived he used our site office as his

headquarters. We also supplied men and materials to carry out emergency works.

That led to problems for me when we came to charge him - but that’s another

story.

One of his jobs is to notify all the

owners and tenants if a building is 'unfit for human habitation' and also what

work, if any, he has had to do to it. That is when the fun started. The DS told

us that this could take a long time because he had to trace owners, their

agents, estate agents etc. But after four weeks everything had been sorted

except the basement tenant of one property (I will call it number 48 for ease

of telling the story). When the DS eventually got hold of the tenant of 48 he

asked who his Landlord was. “I don't know” came the reply. Do you have a rent

book, “Yes”. It must be on that. “No the landlord’s name is blank”. “Who do you

pay the rent to?” “To Bill next door in No 46”. But when they went to No 46,

Bill had no idea who the landlord was either.

It seemed that seven years earlier

Bill’s mate was emigrating to Australia, he knew Bill was looking for accommodation so Bill moved

in. He was told about the arrangement with the basement flat in No 48 and was

given a Post Office Savings Bank Book in which to deposit the money which he

had been doing for seven years. The Account was in the name of the man who

emigrated, and from the amount in it he, too, had been paying money in

regularly for years.

As a Brent councillor, I was

sitting next to James Goudie (now QC), who was the Deputy Leader of the Council

and I recounted the above story. 'Oh yes' said James, 'That is what we call a

Tenancy At Will'.